The Role of Shepherds in Genesis

The Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, lays the foundation for many theological concepts and narratives that resonate throughout both the Old and New Testaments. Among the various roles and occupations mentioned, shepherds hold a particularly significant place. Their portrayal transcends mere profession, serving as a powerful metaphor for leadership, care, and divine guidance. This article explores the role of shepherds in Genesis, examining their significance, key figures, the relationship with their flocks, and the broader theological implications of shepherding in the biblical narratives.

Understanding the Significance of Shepherds in Genesis

In Genesis, shepherds symbolize not only a physical occupation but also an archetype of care and responsibility. The act of shepherding is deeply embedded in the agrarian culture of the ancient Near East, where livestock held considerable economic and social importance. The pastoral lifestyle depicted in Genesis highlights the intimate bond between shepherds and their flocks, underscoring themes of protection, guidance, and provision. Shepherds are often portrayed as figures of authority who lead their sheep to safe pastures, reflecting a broader understanding of leadership rooted in care and stewardship.

Moreover, the role of shepherds in Genesis often intersects with the theme of divine providence. God’s relationship with humanity is frequently illustrated through shepherding imagery, suggesting that just as a shepherd tends to their flock, so too does God tend to His people. This metaphor reinforces the idea of God as a protector and provider, intimately involved in the lives of His followers. The significance of shepherds in Genesis thus extends beyond their immediate context, serving as a precursor to the later biblical depictions of God as the Good Shepherd.

Finally, the portrayal of shepherds in Genesis can also be seen as a reflection of the socio-political context of the time. In ancient societies, shepherding was often associated with nobility and leadership, as seen in the lives of key patriarchs in Genesis who were themselves shepherds. This connection between shepherding and authority highlights the dual role shepherds play as both caretakers of their flocks and as leaders of their communities. The significance of shepherds in Genesis, therefore, is multifaceted, linking practical, spiritual, and social dimensions.

Key Biblical Figures: Shepherds and Their Symbolism

Several key figures in Genesis exemplify the importance and symbolism of shepherds. Abel, the second son of Adam and Eve, is introduced in Genesis 4 as a shepherd who offers a pleasing sacrifice to God, contrasting sharply with his brother Cain, who is a farmer. Abel’s role as a shepherd signifies righteousness and acceptance in the eyes of God, while his tragic fate emphasizes the themes of jealousy and the consequences of sin. This early portrayal establishes the shepherd as a symbol of faithfulness and devotion, key characteristics that resonate through the narratives that follow.

Another prominent shepherd figure is Abraham, who is not only a patriarch but also a metaphorical shepherd of his family and future generations. His life is marked by his leadership and guidance, particularly in his covenantal relationship with God. Abraham’s ability to lead his household and protect his kin reflects the shepherd’s role as a protector and guide. The promise made to Abraham, that he would become the father of many nations, further solidifies the shepherd’s symbolic role as a nurturer of future generations.

Lastly, we have Jacob, whose experiences with sheep herding significantly shape his character and destiny. After deceiving his father Isaac for the blessing, Jacob flees and works as a shepherd for Laban. His struggles and triumphs during this period highlight the complexities of his character and serve as a parallel to the challenges faced by the Israelites. Jacob’s eventual return and reconciliation with Esau symbolize redemption and restoration, reflecting the shepherd’s enduring nature of leading the way toward healing and unity.

The Relationship Between Shepherds and Their Flocks

The relationship between shepherds and their flocks in Genesis is characterized by deep interdependence and mutual care. A shepherd’s primary responsibility is the well-being of their sheep, which includes guiding them to green pastures and ensuring their safety from predators. This relationship symbolizes not only physical sustenance but also emotional and spiritual nurturing. The shepherd’s attentive nature fosters trust and loyalty among the sheep, illustrating the profound bond between caregiver and dependent.

In the narrative of Genesis, this relationship often serves as a metaphor for the connection between God and His people. Just as a shepherd knows each sheep by name, God’s intimate knowledge of His people underscores the theme of divine care and guidance. The act of leading the flock also reflects the shepherd’s role in addressing the needs of the community, highlighting the importance of leadership that is grounded in compassion and understanding. This dynamic relationship emphasizes that true leadership is not merely about authority but about service and sacrifice.

Furthermore, the shepherd-flock relationship in Genesis serves as a model for understanding communal life. The well-being of the flock directly reflects the shepherd’s character and actions. A good shepherd prioritizes the health and safety of the sheep over personal gain, teaching a valuable lesson about selflessness and accountability. This theme is particularly relevant for the community of Israel, as it underscores the expectation that leaders should embody the qualities of a good shepherd, nurturing and guiding the people toward a flourishing existence.

Theological Implications of Shepherding in Genesis Narratives

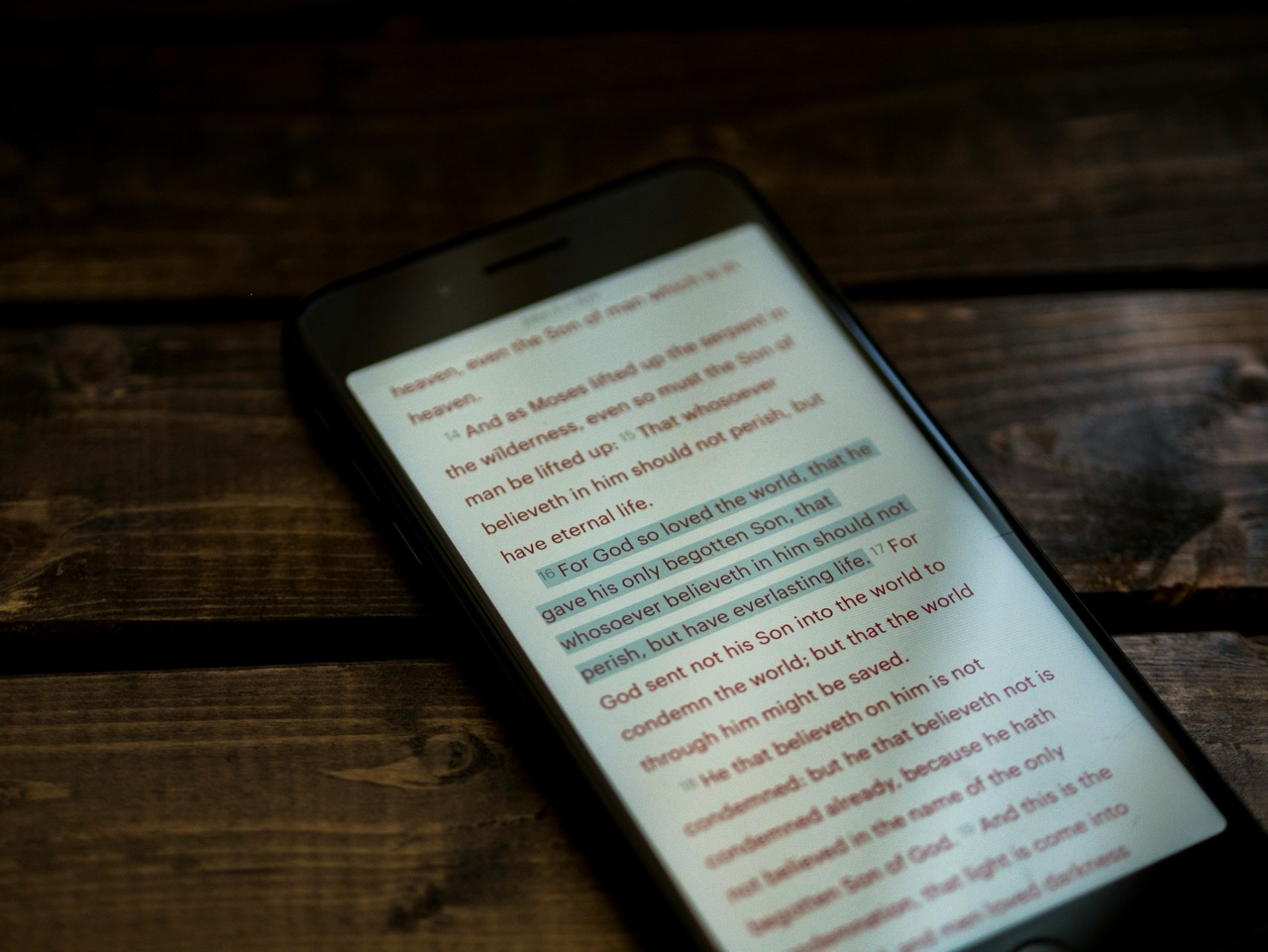

The theological implications of shepherding in Genesis are profound, stretching into the realms of divine providence, human responsibility, and communal ethics. The imagery of shepherding is interwoven with the concept of God’s covenantal relationship with His people. By portraying Himself as a shepherd, God communicates His commitment to care, guide, and protect His chosen ones. This understanding of divine shepherding reassures believers of God’s constant presence and attentiveness in their lives, particularly in times of struggle and uncertainty.

Moreover, shepherding in Genesis raises questions about moral responsibility and ethical leadership. The actions of shepherds in these narratives serve as examples of what it means to be a just and faithful leader. For instance, when Abraham negotiates for the safety of Lot, or when Moses later leads the Israelites out of Egypt, the qualities of a good shepherd—such as patience, wisdom, and dedication—are paramount. This correlation instills a sense of accountability among those in leadership positions, reminding them that their primary duty is to serve and protect those entrusted to their care.

Lastly, the theological implications of shepherding extend to eschatological themes found throughout the Bible. The anticipation of a Messianic figure who embodies the ultimate shepherd role culminates in New Testament references to Jesus as the Good Shepherd. This continuity from Genesis to the New Testament highlights the enduring significance of the shepherd motif in biblical theology, illustrating a divine plan for redemption and restoration that transcends individual narratives. Thus, shepherds in Genesis not only illuminate essential truths about God’s character and human relationships but also lay the groundwork for understanding the overarching narrative of salvation history.

In conclusion, the role of shepherds in Genesis encapsulates a rich tapestry of meanings that extend far beyond the physical act of tending to sheep. Through key figures like Abel, Abraham, and Jacob, we observe how shepherding serves as a powerful metaphor for leadership, divine care, and the ethical responsibilities inherent in guiding others. The relationship between shepherds and their flocks symbolizes a profound interdependence, reflecting the nurturing and protective nature of both human and divine leadership. Ultimately, the theological implications of shepherding resonate throughout the biblical narrative, establishing a framework for understanding God’s relationship with humanity and the profound call to care for one another in community.