The Great Flood: What Genesis Teaches About Judgment and Grace

The Great Flood is a profound narrative found in the Book of Genesis, one of the most significant texts in the Judeo-Christian tradition. This story is not merely an account of a catastrophic event; it serves as a rich theological discourse on the themes of judgment and grace. While the flood represents a divine response to human wickedness, it also highlights God’s unwavering commitment to humanity through the figure of Noah. This article delves into the historical context of the Great Flood, explores its theological implications regarding judgment, and analyzes the theme of grace as demonstrated through Noah’s covenant. Finally, it reflects on how these ancient lessons continue to resonate in contemporary society.

Historical Context of the Great Flood in Genesis

The story of the Great Flood is situated within the early chapters of Genesis, a foundational text that narrates the origins of the world and humanity. This period is characterized by the increasing corruption of human beings, as described in Genesis 6:5, where it states that the wickedness of humanity was great, and every inclination of their thoughts was only evil continually. The narrative depicts a world spiraling into chaos, marked by violence and immorality, prompting God to intervene. This context is essential for understanding the gravity of the Flood as both a divine judgment and a pivotal moment in salvific history.

The cultural backdrop of the story also reflects ancient Near Eastern flood motifs, evident in various mythologies that predate or coincide with the biblical account. However, the Genesis Flood narrative is distinct in its theological framing, presenting a monotheistic interpretation of divine judgment that contrasts with polytheistic views. In many ancient cultures, floods were often associated with deities acting out of frustration or caprice. In Genesis, however, the Flood emerges as a calculated response to human sin, emphasizing God’s sovereignty and moral order in creation.

Moreover, the historical context of the Flood narrative serves to highlight the covenantal relationship between God and humanity. The account of the Flood cannot be separated from its purpose: to cleanse the earth of evil while preserving a remnant through Noah. This duality of destruction and preservation reflects God’s complex nature as both just and merciful, setting the stage for future covenants that will define His ongoing relationship with humanity.

Theological Significance of Judgment in the Flood Narrative

The Flood narrative serves as a stark illustration of God’s judgment against pervasive sin. It is a warning against moral decay and disobedience, emphasizing the seriousness with which God regards human actions. In Genesis 6:6-7, it is stated that God regretted creating humanity due to their wickedness, which underscores the profound relational aspect of God’s judgment. Unlike capricious deities of other ancient mythologies, the biblical God is portrayed as righteous and deliberate, enacting judgment as a necessary response to human choices that betray His created order.

The floodwaters symbolize a cleansing, a divine reset for a world saturated with sin. The theological implications are profound; judgment is not merely punitive but serves as a means of restoration. Just as the waters washed away the corruption, the biblical narrative suggests that through judgment, God seeks to establish a new beginning. This concept is crucial in understanding the nature of divine justice, which is always intertwined with the potential for renewal and redemption.

Furthermore, the Flood narrative illustrates a tension within the divine character—where justice and mercy intersect. While God’s judgment results in devastation, it also affirms His commitment to righteousness. The flood serves as a reminder that while God is just, He does not take delight in judgment but rather desires repentance and restoration. This dual nature of judgment invites readers to reflect on their own moral choices and the consequences that follow, reinforcing the idea that divine judgment is both inevitable and purposeful.

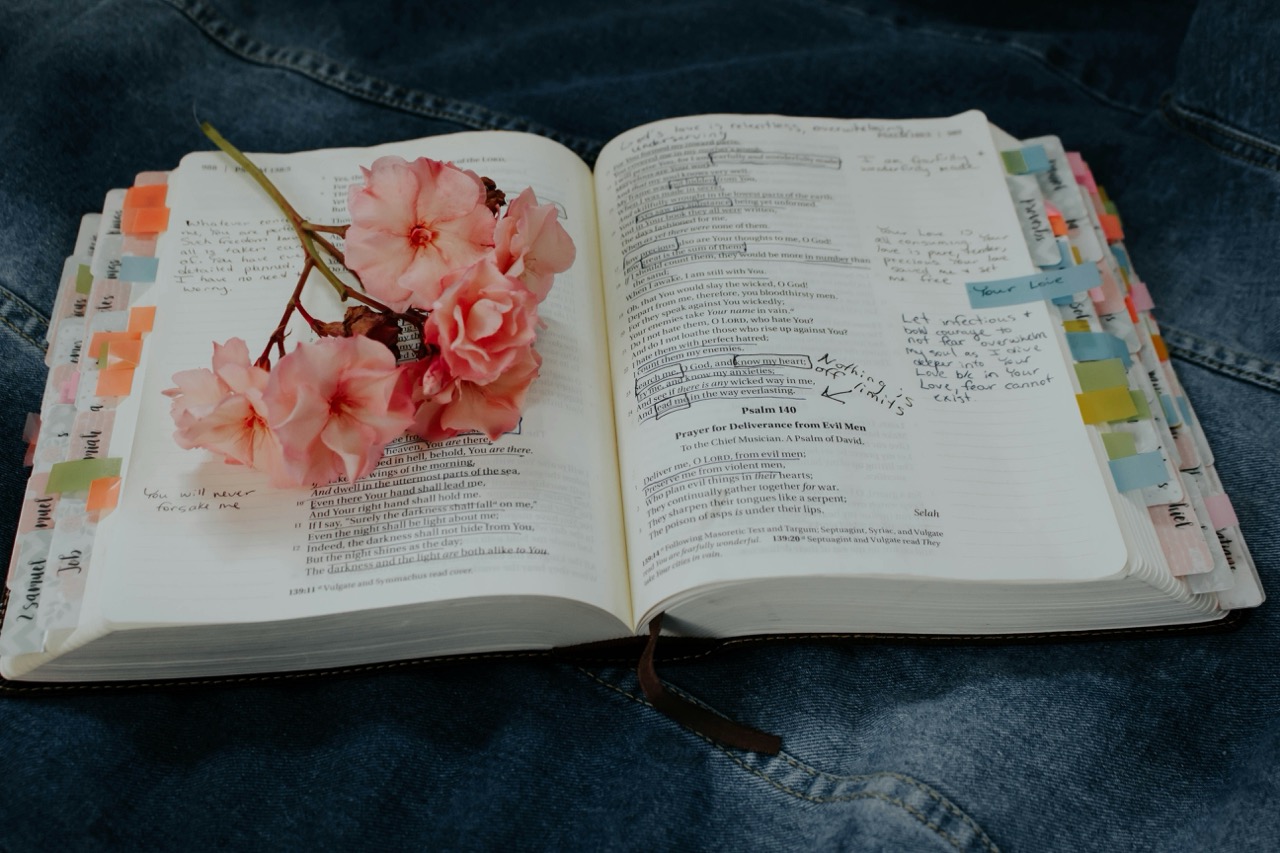

Grace as a Central Theme: Noah and the Covenant

In the midst of devastation, the figure of Noah emerges as a beacon of hope and grace. Genesis 6:8 states, "But Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord," highlighting that grace is not absent even in the face of impending judgment. Noah’s righteousness is not merely a personal virtue; it signifies God’s choice to preserve a remnant through whom a renewed creation could emerge. This selection of Noah illustrates the biblical theme that grace is often bestowed upon individuals who remain faithful amidst a corrupt culture.

The covenant established between God and Noah following the Flood marks a pivotal moment in salvation history. In Genesis 9:11, God promises never again to destroy the earth with a flood, setting the rainbow as a sign of this everlasting covenant. This promise reflects God’s desire to maintain a relationship with humanity despite their failings. The covenant with Noah sets the precedent for future divine covenants, emphasizing that while judgment may come, grace is always available, and God’s faithful love persists.

Additionally, Noah’s role can be interpreted as a foreshadowing of Christ, who embodies the ultimate expression of God’s grace. Just as Noah was the means of salvation for his family and the animal kingdom, Christ offers salvation to all who believe. This typology deepens the understanding of grace as a central theme in the Flood narrative, illustrating how God’s plans unfold through time, leading toward ultimate redemption. The covenant with Noah stands as a testament to God’s continued engagement with humanity, reminding us that grace prevails even in the most dire circumstances.

Contemporary Lessons: Balancing Judgment and Grace Today

The lessons from the Great Flood narrative remain relevant in contemporary discourse, particularly in discussions surrounding justice, morality, and divine grace. The tension between judgment and grace serves as a reminder that while societal sins may lead to dire consequences, individuals can also embody righteousness and be agents of change. In a world grappling with moral ambiguity, the story of Noah encourages a call to personal integrity and accountability, demonstrating that one person’s faithfulness can impact many.

Moreover, the narrative challenges modern readers to contemplate the nature of divine justice. In an era where judgment is often viewed through the lens of cultural relativism, the Flood story invites reflection on the standards by which actions are measured. It prompts questions about how society holds itself accountable and the consequences of collective moral failure. This understanding encourages communities to pursue justice and righteousness while also extending grace and compassion to those who falter.

Finally, the Great Flood narrative compels contemporary society to recognize the importance of covenant relationships. Just as God established a covenant with Noah, individuals and communities are called to create bonds of mutual responsibility and care. The interplay of judgment and grace should inspire not only a personal commitment to ethical living but also foster communal ties that reflect God’s enduring promise. In a world that often prioritizes individualism, the relational aspect of faith emphasized in this narrative speaks to the fundamental need for solidarity and support in pursuing both justice and mercy.

The Great Flood narrative in Genesis serves as a profound exploration of the themes of judgment and grace, offering timeless lessons for modern audiences. It illustrates the complexities of divine justice, revealing that judgment, while necessary, is always tempered by grace. Through the figure of Noah and the establishment of a covenant, the text emphasizes God’s unwavering commitment to humanity. As contemporary society navigates moral challenges, the balance of judgment and grace remains a crucial framework for understanding the divine-human relationship and for fostering a world grounded in justice, mercy, and communal responsibility.